LETTER FROM THE EDITOR: Impact versus intention

Indigo Magazine

When I came to Washburn four years ago, I had attended a private, mostly white Christian school for the last 11 years of my life where I was largely taught what to think, not how to think. I was closed-minded, reluctant to accept other viewpoints and honestly, a little bigoted.

As I met people of all races, ethnicities, backgrounds and cultures, I started to realize that my experience was not a universal one.

My classes challenged me to set aside my own biases and viewpoints and look at issues from other people’s perspectives. I had to stop only listening to people who looked or sounded like me because I was creating an echo chamber for myself. I started listening to social justice advocates, activists and organizations, and reevaluating the ideas I had been taught for the last decade of my life.

I started to open my eyes to injustices and identified the behaviors and biases, both conscious and unconscious, that I held.

I clearly remember a time during my sophomore year when I was working the cash register at Kohl’s. Part of my job was to sign people up for credit cards. A Black man came up to my register to check out. Usually, one of the first things I would ask is if the customer wanted to save 35% and sign up for a Kohl’s credit card. But for this customer, I skipped that question. In only a couple of seconds, I had made the judgment that because this man didn’t look rich to me, he wouldn’t be interested in signing up for a card or wouldn’t be approved. To my surprise, the man asked me to sign up for a card and was approved.

Did I have bad intentions? No. But the reality of the situation was that I had an unconscious bias because of the man’s appearance that caused me not to offer him the deal. Obviously this scenario is not a crime, but it is an action that I have been able to recognize, name and consciously change.

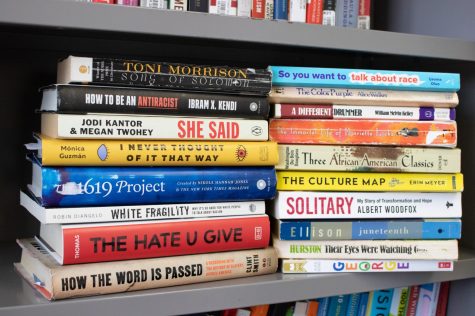

As Ibram X. Kendi recommends in his book, “How to be an Antiracist,” I had to stop saying that I wasn’t racist because I was refusing to see how my actions and words were racist and harming others.

In a conversation with Chris Jones, professor of religious studies, he shared the sentiment that your intentions don’t matter, but your impact does. This stuck with me because I think it is an idea that many of us are missing. We are often quick to defend or rationalize our words and actions, because no one wants to be called a racist. But the reality is a lot of us have said or done racist things. We must name something in order to fight against it.

“We think of racist as attitudes. When we as white people have it pointed out to us that our actions or our words have objectively negative results, we take that as an accusation about our attitudes,” Jones said. “ Then we get defensive, of course, because no one wants to be called racist. And then we shut down and stop engaging.”

We must be intentional and careful in the way we speak and act, because our impact matters. It doesn’t matter if you weren’t trying to create that impact, because in the end, you did. We must also work to become less defensive. If someone takes offense to something you said or did, sometimes the best thing you can do is try to understand why they were offended and change how you act in the future.

“When you’re in a position of power, intentions don’t matter. Results matter,” Jones said.

I’ve had to think about what I want to represent and stand for. I’ve decided that I don’t want to constantly scrutinize others. I’ve decided that I can do so much more good in the world by unconditionally loving and accepting others. I’ve decided that as someone with privilege, I have a duty to use that privilege to be an anti-racist.

I’ve had to identify the privilege I have and the disparities between myself and others. Now, I recognize that I have immense privilege through the many facets of my intersectionality as a person. As a white, upper middle-class, heterosexual cis-female who has never had to worry about not having enough food, healthcare or a house to stay in, I have benefited from unseen advantages.

Not every story in this issue talks about racism, but the focus is on underrepresented, marginalized and oppressed groups. My hope for this issue is that it will be a catalyst for the readers who need a little push to challenge their viewpoints and biases like I had to do.

I ask that you read this magazine with a curious and open mindset. I want you to remove yourself from the situation, put yourself into the shoes of the people in these stories and examine why your beliefs might be different from theirs.

I am far from finished when it comes to learning and growing as a person, but I am proud of the changes I have made and I will continue to make an effort to educate myself.

Forever an Ichabod, Leah Jamison

Your donation will support the student journalists of Washburn University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.