FACULTY COLUMN: Reading to become an antiracist

Indigo Magazine

Naming my privilege: I am a white, educated, middle-class, Christian woman who is married to a man with whom I have two children. I have access to healthcare and own a home.

When I go to the store, I hop into one of our two cars and speed away. If I see a police officer on my way, I generally feel guilty because I am almost always speeding. But I am not worried that I will end up getting shot and killed because I did the wrong thing. When I arrive at the store, I am often greeted with a smile. I am never followed, and I have never been accused of stealing from the store. These things are true for me because of my privilege, and I am foolish if I think everyone is treated the same way.

Racism is real and it happens every day. Many of us infuse racist behaviors into our daily routines without noticing. Being called a racist feels gross and awful, but it’s necessary.

Instead of creating a defensive frenzy, we need to take a good look at the behavior itself. In order to begin a true quest of being an antiracist, we have to be able to call out instances of racism.

In his book, “How to become an Antiracist,” Ibram Kendi says the opposite of racist behavior is not neutral, non-racist behavior. The opposite of racist is antiracist. On page 23 Kendi writes: “To be an antiracist is a radical choice in the face of this history, requiring a radical reorientation of our consciousness.” I strongly recommend his book to anyone who has ever grappled with racism.

Along with clear definitions throughout the book, Kendi takes readers on his own journey of confronting racism at all levels. I had previously read most of the book, but I needed to read it again. Because I was traveling, I ended up listening to the audio book, which is read by Kendi himself, over two days with my husband.

Since finishing his book, I’ve been reflecting on my own journey to live as an antiracist. When I first started attending Washburn’s Center for Teaching Excellence and Learning diversity courses, I felt woefully inadequate and ignorant. Individual Black people have had the longtime burden of representing an entire race, so we must educate ourselves. “What?” I thought. “How do I do this? Is there a syllabus or something?” Amaarah DeCuir presented a couple of CTEL sessions that I was able to attend, and that was terrific.

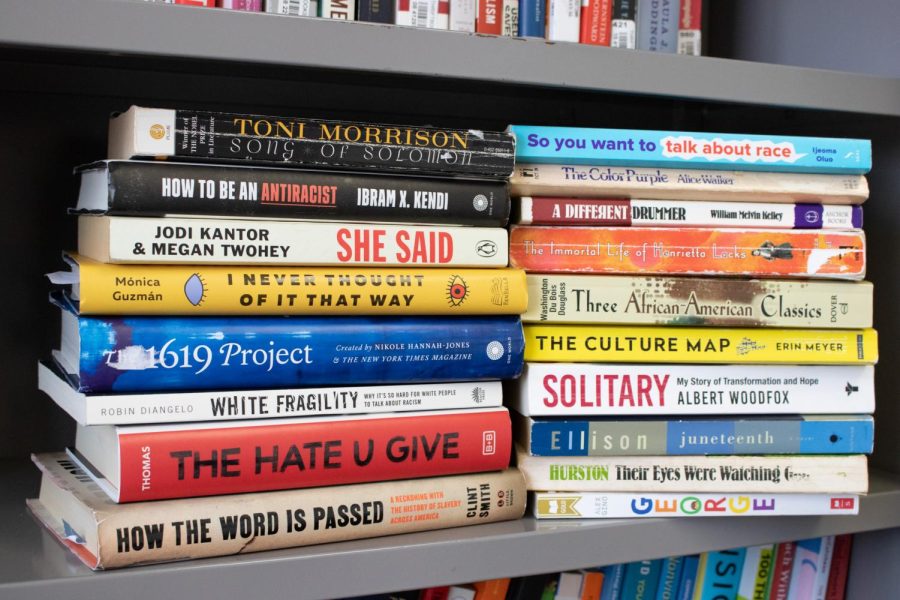

My journey includes taking my class to listen to Olympian John Carlos. I cannot remember who spoke at Washburn when I ended up purchasing a copy of “Teaching Black Lives,” which is a collection of essays written by a diverse group of people. I have the list of essays on a separate tab in my reading list. I remember listening to Ibram Kendi speak in Lee Arena, and this spring I went to hear Albert Woodfox’s incredible story and afterward read his book, “Solitary.”

I purchased and read most of “White Fragility,” and I finally went back and read the last couple of chapters. I have taken page after page of notes as a result of all of these experiences.

I am convinced students do not read enough, so I added a book assignment in my reporting class. One of my Black students reviewed a book by Charlamagne Tha God called “Shook.” For his media-related project relating to the book, he and two other Black men talked about the anxiety Black men face on a podcast. After listening to his almost 30-minute long podcast, I knew I had to read the book. Upon discovering Charlamagne was a radio personality, I decided to listen to it instead. Wow! It was shocking and explicit. But it was also an inside look at an individual Black man’s story— not at all what I expected. I also listened to his book, “Black Privilege,” which has lots of great and applicable career advice that anyone could apply. Looking back, I realize that I was more than a little braggy about how I “bravely” listened to a book a bit outside of my comfort zone.

I purchased more books (see QR code to my lending library). To date, these books, both fiction and nonfiction have helped me gain understanding and depth of perspective. Novels I read include contemporary reads like “The Hate U Give” and “The Other Black Girl.” Realizing I had never gotten around to reading Toni Morrison, I read “Beloved” and “The Bluest Eye,” and I was stunned by the absolute beauty in her writing. I read “The Color Purple,” by Alice Walker and I just finished “Their Eyes Were Watching God” by Zora Neale Hurston this week. I could not put this story down. I finished reading “How the Word is Passed” by Clint Smith, which is a shocking, revealing and compelling book.

A few summers back, I listened to Michelle Obama’s book, “Becoming,” which she reads herself. I’m especially drawn to books that the authors themselves read. It adds something to the understanding. I was super excited to learn that my colleagues in mass media were going to read Kendi’s book and discuss it this summer.

In his book, Kendi refers to reading books and materials by these folks to increase his own knowledge and understanding: Audre Lorde, E. Patrick Johnson, bell hooks, Joan Morgan, Dwight McBride, Patricia Hill Collins and Kimberlé Crenshaw.

I know the work of bell hooks has an important place, and I always have to remind myself why she opted to lowercase her name. I found this quote, and it made me think of something about our need to both assimilate and be individuals in the United States.

In a 2021 article, the Washington Post quoted bell hooks as saying: “I think we are obsessed in the U.S. with the personal,” she continued, “in ways that blind us to more important issues of life.”

Does mainstream equal white America? I think the needle is certainly moving. Growing up, I was taught to think certain things were “trashy”— like tattoos, skin piercings, longer hair for men— and I never once thought about the deeper questions of identity that must come with the judgment about natural conditions like hair and skin. What an exhausting battle it must be to try to always be “code-switching” from one space to the next. We all have our “work faces” and our “friend faces,” but that’s not quite the same thing. We choose these things. And then consider the myriad of ways we rank human beings. It’s pretty gross.

It’s inadequate to be sure, but the one comparison I can make as a first-generation college student is the unmistakable and permanent separation I felt from my family when I crossed over to the “more educated” threshold. It’s always there lurking in the shadows, and I will admit that I have just “played the game” and become the version of myself that is most acceptable to my own mother too many times to count. It prevents deeper connection and yet I persist.

It also reminds me of a lecture from a few semesters back where the idea was that minority students do not ask for help or assume if they do ask, they will receive it. However, white students have no issues advocating for themselves and asking for help and extensions on papers. I wish I had the notes on that in front of me because it was far more eloquent than I am being.

This writing does not have an ending, and maybe that’s appropriate. As individual human beings, will our journey to rid ourselves of racism and all the other “isms” ever truly end?

Your donation will support the student journalists of Washburn University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Linda Tuller • Sep 9, 2022 at 9:01 am

Thanks for this article. I am a white 75 year old grandmother still auditing a class every semester. I have read many of the books but realize I have a long way to go in dealing with my world view. I prefer to use this term rather than anti-racist. My work can only be done one-on-one so I intentionally try to react to everyone I meet accepting their uniqueness and personhood.