Washburn displays “Man Card”

Image courtesy of https://www.themancardmovie.com/watch/

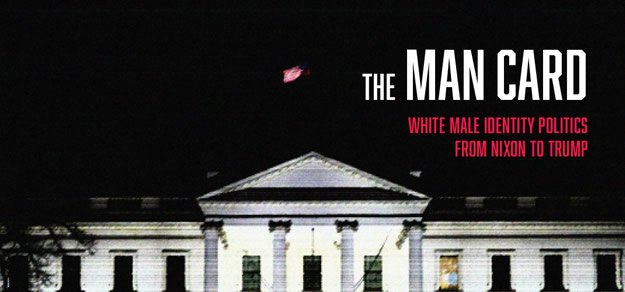

Starkly Political: “The Man Card” is a documentary delving into Republican party tactics to appeal to white men, produced by The Media Education Foundation

Nick Schneider’s Youtube video – https://youtu.be/hjZld70LuAs

The Man Card Film – https://www.themancardmovie.com/watch/

At 7 p.m. on Thursday, Sept. 2, 2021, the Kansas Room in the Memorial Union saw use in the form of a showroom to the film, “The Man Card”. Although originally organized to take place in the Multicultural Intersectional Learning Space, the event changed places in order to better accommodate social distancing. The much larger space adapted well to the handful of students who showed up for the hour-long film and the following discussion. They were able to space out and relax while watching the movie without their face masks on the whole time. The follow up discussion panel was led by Nick Schneider and Nick Solomon, both of whom had unique experiences through their adolescence that shaped how their political ideology was formed; a relevant topic to the film due to their identities as white males.

“The Man Card”, a documentary by The Media Education Foundation, is an informative and political piece that goes in depth over the ways right-wing politicians have commonly employed tactics that appeal to white male Identity politics and has led their party to win several presidential elections in the past. It ranges from the past with President Nixon’s campaign of 1968 to Donald Trump’s recent 2020 campaign for presidency. Melisa chose this movie because it was both interesting, important and potentially empowering to anyone who could be targeted by these tactics against their will.

The discussion panel following the film was led by Nick Schneider & Nick Solomon, who were chosen by Melisa because of her conversations with them through teaching them in class, in which she realized they each had unique perspectives as people who grew up largely identifying as white males, and the target audience of the tactics being discussed in the film. She explained that Solomon was chosen because, “he has a unique perspective of masculinity… because he’s absolutely disgusted with the idea of being a man.” Schneider was chosen due to his past of radical Alt-Right beliefs, and his present state being able to reflect back on and understand why he was drawn to it.

Because of technical problems with the original recording of the discussion, which rendered it unusable, Schneider recorded a solo video of himself rehashing his points from the discussion going into depth about his personal journey in his YouTube video, My Fall Down the Alt-Right Pipeline, How I Got Out, and What I Learned. In it, he explains that through the viewing of a few ‘offensive humor’ YouTube videos, he found himself an observer and participant in several Alt-Right spaces. “There was this large aspect of anti-culture to it, and um anti-authoritarianism to it.” (5:32) – or so it was marketed. And, even as he had doubts, he justified it to himself at the time. “We’re really like punk rock over here, so it’s okay,” (15:25).

Schneider criticizes the film, saying that the part where it pointed out that Trump’s appeal to white men is the move that garnered him success. He would disagree based on personal experience as a supporter at the time. “He [Trump] appealed to me through economic anxieties… and at that point, being eighteen and with a highschool education, I was unable to properly articulate… [that] I had economic anxieties.” (8:00). He also recognizes that Trump’s appeal to economic anxieties was very much disingenuous. “Any capitalist that’s able to win the favor of the working class is committing trickery.” (9:56).

On the timeline of his political beliefs, Schneider remembers that during Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign he was silently active and believing in Alt-Right spaces and in support of Trump. Then, during the first year of Trump’s presidential term, he was able to reevaluate himself and his beliefs as the energetic support of Trump largely died down, and he began higher education, which broadened his understanding of the world and what exactly he was believing in. In 2020, as the 2020 presidential campaigns kicked off, he was then in support of Joe Biden for President, and very much on the left side of the political spectrum.

Looking back, even if he didn’t do much more than observe people in alt-right spaces and add likes to their posts, Schneider feels a deep sense of regret. “I was perpetuating hateful rhetoric. I was in the midst of white supremacists and I was adding to the numbers of groups,” (14:45). He would also theorize that the reason so many white men, especially white teenage boys, seem to be targeted by this pipeline is because they don’t, “fall into any intersectional camps and worry about the types of oppression that [other] people face,” (8:26), he also points out that “it [the pipeline to the alt right] was… a social regression, and so you have less attachment to social norms and you become disconnected from the very just repercussions… and you start to lash out a bit, I think.” (20:10). Which suggests that it provides a sort of relief to people struggling with – oftentimes just – criticism over their actions, a common commodity sought among teenagers who are first learning social norms.

Edited by :Ellie Walker, Katrina Johnson and Simran Shrestha

Your donation will support the student journalists of Washburn University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.