Your donation will support the student journalists of Washburn University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

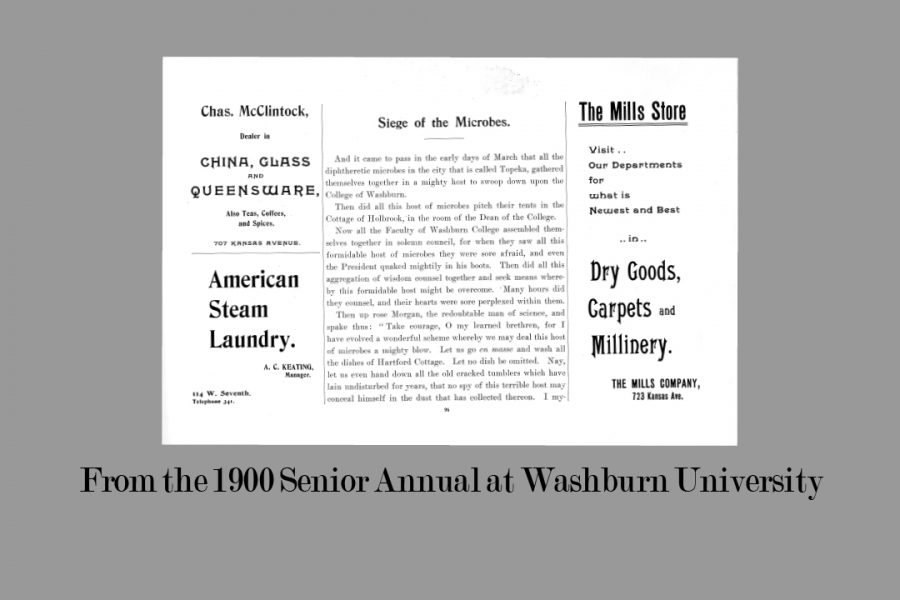

1900: This article appeared in the 1900 Senior Annual of Washburn College. 2020: People and Plague: Human’s interactions with disease outbreaks has left a mark on us. The long-term effect the Coronavirus has had on the world is still uncertain.

Washburn faculty hold conference on past pandemics

November 28, 2020

A panel made up of Washburn faculty, alumni and other distinguished guests gathered Thursday, Nov. 12 at 7 p.m. to discuss the impact of past disease outbreaks on various human cultures throughout history.

The panel was put together by the honor society Phi Alpha Theta and led by History Professor Thomas Prasch with the purpose of discussing the great pandemics of the past, which go by the infamous names of the Spanish Flu, the plague of Justinian, the Black Death and more. Five speakers in total took turns presenting their topics to the Zoom audience, which had almost 25 people in attendance.

“It’s not like we haven’t been here before,” read the poster advertising for the discussion.

The first speaker of the night was Kerry Wynn, history professor and the director of the honors program, who gave a presentation on indigenious people and pandemics. She spoke mostly about how the Native American Cherokee Nation faced off against early colonists and the diseases that they brought with them in the form of smallpox.

She also noted how modern perceptions of the smallpox outbreaks among Native American tribes needed to change as Europeans are depicted as the “unwitting beneficiaries” of the outbreaks.

“Historians are really starting to push back against this vision of pandemics and say that we need to study disease in its context,” said Wynn. “We need to understand that when we look at diseases, human actions and state structures have a very large impact on the progression of disease, the way it’s experienced and that pandemics in North America and North American history are not simply these independent agents, but they are part of colonialism.”

“There is a violence of colonialism and genocide as a total system or process in which disease is only one part,” said Wynn.

The second speaker was Tony Silvestri, lecturer in history, who highlighted one of the worst, and first, global pandemics humanity faced: the Black Death. The disease ravaged Europe and Asia, taking with it over a third of the human population at the time, and has haunted the memories of scholars and historians alike since it first appeared in the mid-14th century.

He explained how the plague first devastated China before making its way to central Europe in the bellies of trading ships filled with rats carrying the Black Death.

“Some estimates show that upwards of 90% of the population of China was killed,” said Silvestri. “By 1351, China had lost at least half of its population with two-thirds being a high estimate.”

Silvestri continued by explaining similarities between COVID-19 and the Black Death, including the spread of misinformation and the passing of blame to certain ethnic groups.

“One expert said not to eat cold lettuce, another expert said to add vinegar to everything. One guy argued to eat as much fish as you can, the other said, ‘don’t eat any at all’ while another said not to eat slimy fish,” said Silvestri. “Probably the most dangerous, and yucky parallel between then and now is the blaming of people. There were pogroms against Jewish communities all over Europe, and some really vicious ones, as a result of the Black Death.”

A pogrom is an organized massacre of a particular ethnic group.

The next orator was Brooke Manny Wells, a graduate research and teaching assistant at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and Washburn alumnna, who talked about the 1918 pandemic that is commonly referred to as the “Spanish” flu.

She spoke about the impact that the flu had on the rural areas of Kansas as most historians glaze over how isolated communities dealt with the pandemic.

“You see a lot of rural areas who they’re either misdiagnosing, they’re not being able to diagnose the flu at all, and so you’re missing a lot of the numbers,” said Wells. “The estimated impact is probably larger, greatly larger than the recorded numbers during this time.”

Fourth in line was Dustin Gann, an assistant history professor at Midland University and also a Washburn alummus, who followed up on the discussion about the 1918 pandemic with a poem titled “Our Vacation” from that time period.

Gann focused his portion of the discussion on schools and universities near Omaha, Nebraska, during the 1918 flu.

“I’m looking at them through the student publications, the newspapers or the yearbooks that were published during this period to try to see how students on campus, college students, how they experienced and really interpreted this idea of flu,” said Gann.

The fifth and final speaker of the evening was a lecturer from the English department, Liz Derrington. She gave a lecture on a more modern and ongoing disease outbreak: AIDS.

Derrington highlighted how AIDS has been recategorized multiple times on Wikipedia as various internet sources argue over whether it should be classified as a pandemic or as an endemic, citing official talking points from the World Health Organization.

General discussion continued for half an hour after Derrington finished her presentation where students and other attendees were allowed to ask their questions.

“We’re all in this together, everyone can be affected by this. We all have ethical responsibilities to each other,” said Derrington.