Dissecting the John Curry Mural at the Capitol

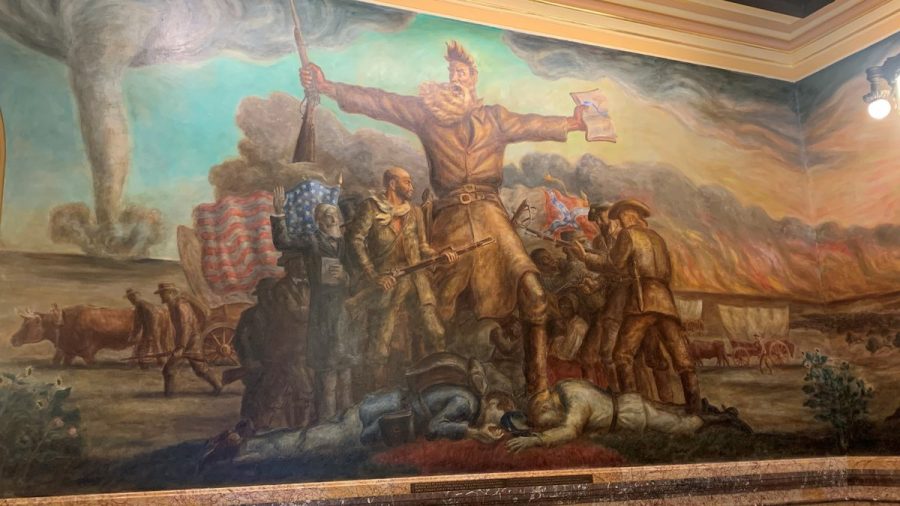

On display: The Topeka Capitol building is host to many murals including this one by John Curry.

When one searches for John Brown, one of the first artistic results is a mural not three miles from the university. It is on the second floor of the State Capitol, Brown towering over any viewer who steps up there. Yet there is much more to it than a wild man clutching a book in one hand and a rifle in the other.

The image known as Tragic Prelude is not just its most famous component. It is a three-part piece, with one painting depicting Father Padilla and Coronado overlooking the “Kingdom of Quivira,” and another of a plainsman standing in front of a felled buffalo. It then becomes the icon of Bleeding Kansas, with Brown at the center, almost cutting off the lesser men around him. The work, when viewed as a whole, provides a more complete understanding of pre-state Kansas, and to take the work out of its context confounds the artistic intent.

Such was what its artist said. John Steuart Curry, the painter of the mural, was commissioned in 1937 to create a work for the Capitol. The money came not from the state but from William Allen White, another notable Kansan. When the work was completed, the state legislature rejected it for its perceived defects and refused to hang it in the Capitol. They did not like that it portrayed John Brown as a maniac, the violence that heightened the tension and the calamity on the horizon. They felt it ridiculed the melodramatic parts of Kansas and portrayed it in a negative light. Insulted by this, Curry returned to Wisconsin, the state where he was employed. He would never see the painting hanged in his lifetime.

This is a tragedy, though it is one that has been rectified except to those it concerns. Far from a work that glorifies the rural and fanatic nature that the Legislature criticized it for, the Prelude is a work that captures the violence of its time well. It may be menacing, but that is because the time it seeks to emulate was so. The 1850s were characterized by their violence, in Europe as well as America, and men across the world rose to offer their personal ideals to that. John Brown towers over his controversy just as he towers over the other participants in the mural. He casts a shadow over history, a man who is more akin to myth than breathing humanity. There may be a calamity coming, and he is responsible. But so too does his ideal, and it towers higher above the center.

The work has been criticized for its tawdry nature and undesirable subject prompted controversy in its day and ultimately became part of a system that once hated it. That is the history of the ideal of Kansas. There are aspects of life we wish to remove and will do anything to not be seen as backward or melodramatic. Only through confronting these may we rise past the superficial and see the ideal as it truly is.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Washburn University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.