Physics major calculates ‘Star Wars’ logistics

May 24, 2016

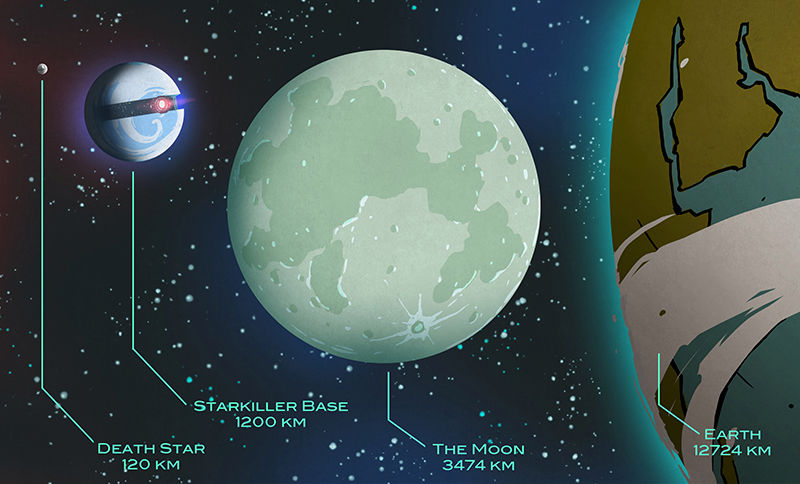

After seeing “Star Wars: The Force Awakens” in theaters and watching the colossal Starkiller Base suck up the power of a star to destroy planets halfway across the galaxy, Mindy Townsend wanted to test the viability of such a terrifying weapon.

Townsend, who only last week graduated from Washburn University with a degree in physics, said she remembered how the super weapon operated by sucking up all the mass of the star it was orbiting.

“I thought, ‘Ah, that’s not going to work. The orbit is going to change,’” Townsend said. “I just wondered how it was going to change, and I realized I can solve this problem. This isn’t too difficult.”

After leaving the theater, she went to work on the problem. As the dwarf planet-sized super weapon charged its main cannon, it sucked in the energy of the star it was orbiting. Townsend wanted to know what the orbit of both the star and the planet were doing.

She explained how when two bodies are orbiting, they are actually orbiting a common center of mass, called a barycenter. So while Starkiller Base was orbiting the host, the star itself was also doing a very tiny orbit around the center of mass of the whole system.

Townsend said by the time school started again in January, the problem was mostly solved, with only minor bits needing to be refined.

“It wasn’t too complicated of a project,” Townsend said. ”Just something I wondered about, and I did it.”

Townsend was finishing up her third and final year at Washburn. She had previously earned a bachelor’s degree in political science from Pittsburg State University in 2007 and graduated from Washburn’s School of Law in 2010.

Seeing as the recession was stunting the economy and job market, she decided higher education was the right way to go.

“I decided I hate [law] anyways, so I might as well try something fun,” Townsend said. “This was fun.”

She said she had an interest in physics and science before, but she never really liked the math.

“It was always just frustrating because I never really quite had the math skills to really understand physics,” Townsend said. “It was never something I was just naturally good at, so I just quit.”

Now she is solving differential equations for fun – something that you take after Calculus 3 – in order to understand what Starkiller Base will do as it eats its host star to power the ultimate terror in the galaxy.

She said that there are really only two orbits you have to worry about in the problem: the orbit of the base and the orbit of the star.

“It turns out when you do of the requisite math, the orbit of the base ends up depending on the mass of the star and not of its own mass,” Townsend said.

The same goes for the star. She tested both scenarios – one where the base was taking on mass and one where it wasn’t. For the base, it didn’t matter how massive it got, the orbital path would be the same – it would slowly start to curve into a straight line.

“The star is a little more interesting,” Townsend said. “Its orbit, how it changes, depends on whether the base is taking on mass or not.”

She said when the base does take on all the mass of the star, it can really be seen from the orbit plots on a graph that the star is being pulled toward the base, really dramatically.

“It’s almost like they are trying to change roles,” Townsend said. “The center of mass is being shifted over to the base. If the rate of decrease [in the mass of the star] had taken longer, we may have seen the star start to orbit the base.”

Townsend said people asked her what the point of solving this problem was. She told them that she just wanted to know what it looked like.

“I just went into this just doing it for fun,” Townsend said, “I wasn’t planning on presenting at Apeiron or anything like that. It kind of took on a life of its own.”

Townsend said her problem growing up was she was into a lot of different things. If something wasn’t “clicking” for her, like math, she just went on to the next thing.

Townsend said when she was a kid, when math first started to get hard she didn’t have the personality to stick with it. She said she didn’t see the payoff. But, just getting a little older, she did see that.

“It’s rewarding, though, to be bad at something, and then be kind of OK at it, eventually with a lot of practice,” Townsend said. “That’s not to say that it’s not really, really frustrating a lot of the time. It just took a lot more work than anything else I tried to do.”

Townsend said it got to the point where she would do something she was really bad at, or do nothing at all.

“It was one of those put-up or shut-up moments, where you keep complaining about my life or I could attempt to understand something I’ve always been interested in,” Townsend said. “So that’s what I did.”

Townsend’s next pursuit is to get a doctorate in physics at the University of Kansas. She will start in the fall.