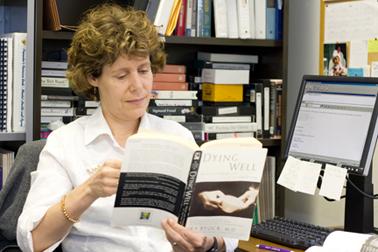

Professor working to improve end-of-life care

April 14, 2008

While the discussion and understanding of death and dying can be uncomfortable and difficult for many, people like Deborah Altus are invested in presenting a clearer vision.

Her work as a gerontology researcher for more than 10 years, coupled with her Ph.D. in psychology, have aided her in delivering quality information on the process of aging to her students in the classroom as well as in the community.

In spring of 2009, Altus, an associate professor in the human services department, will take a sabbatical to further her research in these areas. Altus plans to use her research to prepare curricular materials related to end-of-life care. In addition, she will examine state statuses and county/local ordinances related to funerals, embalming, burial, the transportation of bodies, advance directives and artificial nutrition and hydration.

“My hope is to continue the focus on improving the process of end of life care and death and dying in Kansas,” said Altus. “Research shows that people don’t usually die according to their previously requested wishes and that is something that must be made better.”

Through serving as the co-chair of a public engagement task force program called Living Initiatives For End-of-Life Care, also known as the LIFE Project, Altus has been able to communicate and work with a coalition of many organizations that are all working together to improve end-of-life care. The LIFE project’s mission is to help all Kansans with advanced chronic and terminal illnesses live with dignity, comfort and peace. The Association of Kansas Hospice first assembled it in February 1998.

Altus explained that the program recently received a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson foundation that went toward three separate yet equally important areas, each of which she hopes to touch on in her own research and interaction with the community.

The first of these areas dealt with the legislative portion of end-of-life care. More specifically, this includes such items as the advance directive, which explains to a patient’s doctor what type of care they would like to have if it just so happens that they become unable to make their own medical decisions.

A living will is one type of an advance directive. It is a written, legal document that describes the kind of medical treatments or life-sustaining treatments a patient would want if he or she were seriously or terminally ill.

While the living will doesn’t allow the patient to select someone to make decisions for them if in fact they become unconscious, the durable power of attorney does this exact thing. It is generally more useful than a living will.

Altus said that while most people say that they want some sort of an advance directive, very few actually go about completing the required forms.

“They think they need a lawyer or a special witness, and since many patients might not have those types of resources they fail to fill out any type of advance directive which, in turn, causes a number of problems if they become unconscious,” said Altus. “The truth of the matter is that you don’t need a lawyer or special witness to get these forms completed. The paperwork is quite simple.”

The second portion of the grant went toward professional education to better inform doctors and medical students on how to more effectively treat pain.

The last portion of the grant went toward the community. Altus’s hope, along with that of the LIFE Project, is to aid and enhance the process of communicating with people who are dealing with the legalities of the funeral process. Altus said that many families which have lost a loved one end up getting taken advantage of by the funeral industry.

“Kansans need to know about their options and, furthermore, what is legal and illegal on the part of the funeral home,” said Altus. “They need to be guided toward the better questions to ask when they are grieving and trying to organize a funeral all at the same time.”

The overall improvement of lives overall seems to be one of the main missions for Altus. Through teaching the Death and Dying course at Washburn, she is able to reach a wide range of majors ranging from the health care professions to that of the helping professions.

“I’ve always wanted to do research in a profession that is useful,” said Altus. “My hope is that people can take my work and apply it in their own lives.”