The Who celebrate 50 years of revolutionary rock

April 24, 2014

Four working class young men from Shepard’s Bush, London forever changed the look and sound of Rock music 50 years ago this April. A handful of months after The Beatles sang “I Want To Hold Your Hand” on the Ed Sullivan show, The Who exploded into the rock scene with a sequence of aggressive G chords, a thunderous bassline and the battlecry, “I Hope I Die Before I Get Old.” After they blew the audience away with their revolutionary sound, they smashed guitars and exploded their drum sets with dynamite.

The Who sung about discontentment and engaged in destructive art 13 years before anyone would use the word “punk.” Nearly 10 years before anyone had heard of AC/DC, The Who had already been using distorted power chords with roaring vocals. They pioneered the concept of a continuous narrative in Rock music with “A Quick One While He’s Away” and released the first true rock opera “Tommy.”

Each of the four members of The Who are undisputed Rock legends in their own right. Roger Daltrey, the vocalist, is one of the most powerful faces in rock ‘n’ roll. Daltrey’s performance at Woodstock, as the sunrise bled through the fringe on his outstretched arms, is the archetypal image of the golden Rock god. Pete Townshend, the guitarist, would play until his fingers literally bled during intense solos on songs like “Sparks” and would finish the sets in a berserker’s rage, destroying his guitar and Marshall stacks of amplifiers.

Nobody picked up a bass guitar after 1965 without having to bow down before John Entwistle. The driving force of The Who’s unique sound was the raw power and unrivaled talent of Entwistle’s bass playing. Keith Moon’s drumming style was unique and his wild tendencies toward excess created the stereotype of rock ‘n’ roll hedonism, ultimately serving as the inspiration of the Muppet’s character Animal.

They were a band unlike any other. They churned out numerous studio albums that rank among the quintessential records every collector needed to have to prove their worth. They influenced many great bands, including Queen, U2, Pearl Jam, The Flaming Lips, The Jam, The Sex Pistols, Oasis, The Stooges and The Ramones.

As a live act, they were larger than life. They were forced to stop playing venues with general admission after an incident in 1979 where 11 concertgoers were trampled to death in Cincinnati. “Beatle mania” may have been powerful, but the riots over The Who were downright dangerous.

“The one thing that disgusts me about The Who is the way they smashed through every door in the uncharted hallway of rock ‘n’ roll without leaving much more than some debris for the rest of us to lay claim to,” said Eddie Vedder, the lead singer of Pearl Jam in the notes of the 2001 album “Substitute: The Songs of The Who.”

The Who appeared on “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour” in 1967 and took their destructive performance style to a new level. Without the knowledge of his fellow bandmates or the crew of the show, Moon had bribed a stagehand with whiskey to rig his drum set with 10 times the amount of explosives as planned. The explosion is often blamed as the cause of Townshend’s hearing damage. In today’s rock ‘n’ roll culture, it seems unimaginable to have unplanned explosives in a television studio.

The Who were born out of the mod subculture, which was the foreground for “Quadrophenia,” a revolutionary Rock opera released 40 years ago. The album tells the story of Jimmy, a young mod who is struggling to find his path in life. Jimmy has four personalities: the rebel, the romantic, the lunatic and the hypocrite, each of which is brought to life by one of the four members of the band.

“Quadrophenia” was a magnum opus that spoke to the common identity struggles of teenage males who struggled to fit in. Lesser bands try to appeal to struggling teenagers through superficial suburban angst, but The Who tackled all of the complexities and hypocritical components of identity crises.

The protagonist sings about being compelled to fight with his parents while knowing that in the end he still lives under their roof and shouldn’t complain. The album addressed the discontentment with becoming another number in a crowd of lost youth, being fated to fade away as an invisible laborer or identifying as one of many uncool men who struggle to stand out to the women they pursue.

One of the unique things about The Who was that although they were undeniably successful, they wrote songs for the uncool. “The Kids Are Alright” starts off with watching another man taking a guy’s girlfriend and realizing that he may as well leave her behind.

The protagonist in “Substitute” was born with a “plastic spoon” in his mouth and in the song “Bargain,” the protagonist states that to win this girl’s affection he would suffer anything and count himself lucky. In “Behind Blue Eyes,” the lyrics talk about the unbearable burden of pain that men are supposed to hide through callused anger. The Who wrote anthems for the faceless numbers in the crowd fighting for a break.

I was introduced to The Who from birth because my father was an obsessive fan. At the age of 3 or 4, all I wanted to do was be a member of The Who. While other kids wanted to go to the moon, I wanted to smash guitars. Eventually, everyone gets older and realizes some dreams have to be reworked for practicality. I stopped dreaming about being in The Who and transitioned to wanting to start my own band.

When I was 5 years old, my father and I travelled to Chicago to see The Who in concert. It was one of the most influential moments in my childhood. By the time the concert ended, the buses were no longer running to United Center. We had to hitchhike through Chicago in the middle of winter, but it was well worth it.

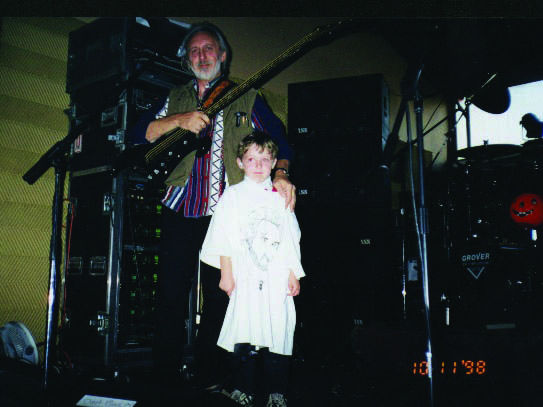

When I was 7 years old my father took me throughout the Midwest to various bars to watch Entwistle play in his solo band. At age 7, I met Entwistle for the first time in a pub in Nebraska. Not many kids get to meet their hero and fewer get to do it on more than one occasion.

I count myself lucky to have been raised on The Who. I would credit “Quadrophenia” for helping me through adolescence. I was born 18 years after it was released, but it was the most important album to me while I navigated the invariably difficult path to adulthood.

I wasn’t part of the mod generation, but psychosocial elements of the Rock opera fit perfectly with my struggle to find my place in life. The impact that record had on my social identity inspired me to conduct an independent study in sociology analyzing the functions and meanings of Rock albums.

I would argue that sociologically, The Who is still relevant after 50 years. The majority of their songs were not simply a product of popular trends specific to the ‘60s and ‘70s. As an example, I would direct any college graduate that can’t find a job to “Young Man Blues.”

Categorizing The Who as just another British Invasion-era band is missing the Amazon Rainforest for the twigs. No other group pushed Rock to such limits. Debates rage on between record collectors about The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, but The Who are a different breed.

The three bands fit into the holy trinity of British Rock, but The Who were the loudest, wildest and most destructive revolutionaries of their generation. In 1965, Daltrey shouted, “I hope I die before I get old.” After 50 years, some could argue they failed to live up to that rock ‘n’ roll mantra. In truth, they can’t die because the music will never get old.